How to dress to attend a classical music concert

03/08/2023 - Thiago de Paula RochaHow to dress to attend a classical music concert?

Classical Music Concerts, how to dress to attend one, and Concerto, the musical form that named the social event; also, a famous vest.

Whoever thinks that attending a classical music concert is a special occasion may have contrasting expectations when thinking about dressing for it: on the one hand, it is the joy of those who like to dress up; on the other, it unsettles those who want to get ready but do not know how. There are also those people who do not bother with the subject and just go – which is excellent and is in line with the recommendations of orchestras and concert halls.

This text tells a little of what a concerto is, the type of musical composition that gave the name of the event known as classical music concert; gives modest tips on how to dress to go to such a social rite; and remembers a famous vest.

Concerto, the music

The social concert rite inherited its name from the musical form concerto, a word whose origin refers to the conjunction of the Latin terms conserere (to gather, to participate, to join) and contest (contest, competition, dispute). In this type of music, two characters dialogue: the soloist or instrumental solo group and the orchestra.

In the beginning, the concerto was the music that had instrumental and vocal parts independent of each other (as opposed to those songs in which the instruments played the same lines sung by the singers) Saul, Saul, was verfolgt du mich? (Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?) by Heinrich Schütz is an example of this type of sacred concert.

The concerto form gained autonomy from the vocal music and became what is called Concerto Grosso, a style in which some instruments play solos accompanied by a small orchestra. An example of this concert type is the Concerto Opus 6, n. 2 by Arcangelo Corelli.

When separated from its vocal tradition, the concert form became a type of music played by a soloist & orchestra (sometimes more than one soloist, but usually only one). Examples of this type of concert, which is the most popular and archetypal one, are Concerto para Flauta (Wq. 22), by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (yes, son of that Bach); Concerto para Piano, Opus 54, by Robert Schumann; and Alban Berg's Violin Concerto (“to the memory of an angel”).

In the twentieth century, music retook the Baroque conception of Concerto Grosso – a concert in which the soloist was and emerged from within the group –; it is when concerts for orchestra and instrumental groups were born. For instance, consider the masterful Música para Cordas, Percussão e Celesta and the Orchestra Concert by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók.

The music from the centuries covered here is, therefore, classical. However, there has been popular music in those same centuries, for example, in villages, public fairs, houses, parties, etc. The point is that classical music does not descend from popular music as it descends from other social practices, so we will not approach it in depth.

Concert Etiquette

“At a certain moment, a habit of organized listening arose in European society and – as a byproduct of this habit – the establishment of public and private concerts. In other words, there was a point in history when audiences fell silent. After that, music took on a new meaning as an act of solemn communication occurring in another space from everyday life. Instead of being a background, something that was never more prominent than when being danced to or sung, music became an object of attention for its own sake, a ‘real presence’ before its hushed congregation.” (Roger Scruton in Understanding Music)

As we might predict that it would happen, the collective situation known as a classical music concert has been considerably altered over the centuries. It accompanies the history of clothing – seen in the rich collection of Wikipédia images.

The following is a brief overview of concert etiquette and ceremonials and how they have changed throughout Western music history.

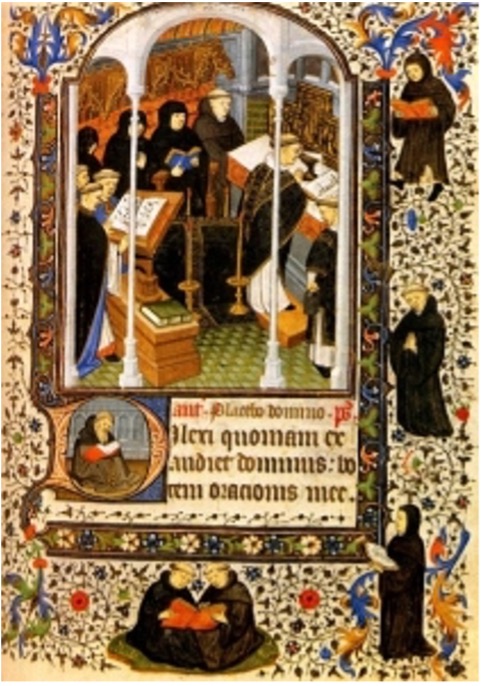

From Middle Ages to Renaissance: mainly in the Churches

The music that we know today as classical descends mostly from cultured religious music, especially from the Christians. For many centuries the Church, especially the Catholic Church, was the most excellent guardian and producer of classical music.

In Catholic rites, praising God was (and is) the ceremonial focus. Naturally, it was expected (and still is) from those present an attentive reserve, respectful silence, modesty, and temperance. That is why the garments had (and have) the obliteration of individuality as their primary objective.

The music and not the musicians exalted the Divine, just as the church elevated it with its architectural and often pictorial materiality.

Classical concert music has inherited this tradition, so black is the most common color for musicians’ costumes.

Thus, in the first centuries of Western music, the faithful and the musicians (themselves faithful, too) dressed to commune and submit to Providence from the tenth to the thirteenth century. It is important to remember that this musical production was intended to enlighten, not to entertain.

From Baroque to Classicism: courts

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, classical music left the churches and headed for the residences of the nobles. As a direct consequence of Europe’s significant changes, the rite of listening to classical concert music changed, just as the costumes changed together. It also changed the primary purpose of music, which became the entertainment of European courtiers.

The courtiers listened to music in their homes in two ways: at dinners and the like and in private concerts.

That is, they listened to a lot of music in the same way that so many people do even today: while eating. Functional music, therefore.

Although they had good manners and protocols, they were, after all, in houses, not kneeling in an imposing church. Mozart and their contemporaries knew that their musical performances could be interspersed with conversations, dishes, cutlery, bowls, and everything else that makes up the soundscape of meals.

These people also listened to music in private recitals.

These were extraordinary events, even though they did not happen with the audience in absolute or religiously reverential silence.

Adults and children wore clothing, makeup, and accessories to match the event’s glamor and to project or reaffirm a social position with which they wished to be identified by their peers (similar to today's events, by the way).

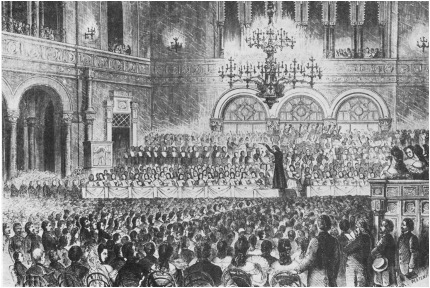

Romanticism: concert halls

In Romanticism, classical music became the focus of the rites in which it was performed, keeping up with the secularization ongoing in the society that produced it. The music and the musician then became protagonists of this society.

This change led to the emergence of concert halls in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Besides being a genius of piano, composition, and a performer like few, Liszt was adored and worshiped by the European public, that fiercely disputed places in his concerts, to which they went with clothes chosen judiciously. He was famous for his masculine and mysterious manner of dressing and relating to his audience.

hat remained in the history of music is that Liszt awakened a level of sparkle that in the twentieth century would be characteristic of pop stars like Elvis Presley. By Liszt’s time, the purpose of music was consolidated as entertainment.

But even in the nineteenth century, people would attend operas in a stir that we would recognize more in food sales fairs today.

It is said that in 1882 the composer Richard Wagner scolded the audience of Bayreuth in a performance of the opera Parsifal. It is hard to prove that this happened. However, it is highly feasible that it did because the public music hierarchy was changing.

In the article The History of Concert Etiquette, Abridged by Crystal Chan, Gustav Mahler, with his Kindertotenlieder (Songs for the Death of Children) in 1905, was the first to specify in a music sheet that the audience should not applaud the songs individually, noting that these were a unified set, and making it clear musicians should not be hindered – as we can see in the image highlighted below.

At this point in the history of European music and society, the public appreciation of music was changing. The musician, the individual musician, was the object of worship. The musician was no longer the medium, but the ultimate purpose, a purpose in itself.

Twentieth century: concert halls become “churches”

In the twentieth century, there was the joining of the reverential posture, which was once a holy thing and was now destined for music, with the level of worship of the musician that arose in Romanticism.

The audience and the classical musicians dressed and behaved willingly, accepting that music is the protagonist most of the time, leaving the attention to the soloists, emphasized precisely by their attire.

It was agreed that there would be applause only after complete pieces and not between their parts (movements), except for the opera (a context in which effusive congratulations “bravo” and applause are well accepted after the soloists' excerpts, the arias). There was a progressive worship of the musician. Thus, the musicians were seen as demigods and even influenced national elections. We could think of Luciano Pavarotti and Bono Vox. These musicians were listened to by billions of people. As a result, they achieved economic and social power.

In the twentieth century, it appeared the first professional musician who became a billionaire directly due to its musical production. And there were some more already.

Twenty-first century: classical shows

Even with orchestras and concert halls repeatedly saying that there are no (restrictive) dress codes and practically playing in a simple suit, often without the vest – the piece that would initially make up the trio that forms the complete ensemble that is the suit – there are people who, like conductor Baldur Brönnimann, who credits the fails of classical music as a whole to the way classical musicians dress. In his article, Ten things we should change in classical music concerts Brönnimann states: “I don’t think the perception of an orchestra changes by simply playing in colored shirts, but tail suits are out. Too 19th century. There are classy and much better-looking suit options around”.

Fortunately, some people argue that classical music can continue to be what it has been over the centuries we know. That is what the composer Aaron Gervais defended in his article Concerts of classical music are great – stop apologizing for them. “These days, everything is informal. Especially here in San Francisco, it’s not even safe to assume people will dress up for weddings. So when classical ensembles put on their penguin suits, the concert stands out. And when it comes to entertainment choices, people go for things that stand out.” Gervais highlights in the same article the success of the chamber group Elevate, which insists on a strict dress code for its musicians. Elevate has won a loyal audience “not by making things convenient, but by demanding that the audience rises to its standard”.

Gervais states, “As I wrote some time ago, you will never hit Netflix in terms of ease and accessibility. There is too much competition for people's time. You have to compete in exclusivity. '' With the Digital Concert Hall, the Berlin Philharmonic looks at this situation. The application has brought classical music to the world of video on demand and, in the Netflix way, to streaming. Televisions, computers, cell phones, and tablets will likely receive the best orchestra in the world. Still, what you have for DCH is transferring a digital file. There is no 4k that replaces the experience of listening to music with sound in its purest and real immateriality.

Speaking of digital files, it should be remembered, according to Gervais – but now quoting the article The classic is not dead, and stop comparing it with pop already, classical music is at risk too in the, by itself, malfunctioning CD market; it only sells more than jazz.

Another current demand for classical music concert halls is that they incorporate some technological novelties and entertainment habits common to other styles of music, such as the consumption of drinks during the show, extravagant lighting effects, video projection, etc.

Classical music concerts will benefit from some (not all of them, not any) technologies. However, classical music also has the advantage of choosing when and what technology to adopt, as there are other styles of music and different types of musicians experimenting and testing it and, in practice, being test subjects for the experiments they choose to do. That is the case of electronic pop music, which is at the forefront of incorporating non-musical technological elements and continues to evolve in this direction, as Vas Panagiotopoulos in The History (and future) of Live Music shows.

Even someone who never went to a concert has heard a lot of music derived from classical music, whether in movies, TV series, or electronic games. Video game music is the soundtrack of a generation. This can be harnessed to bring youngsters into concert halls, as orchestras play music made for games or movies. There is also traditional classical music in a considerable sum of these concerts.

Another doubt that pervades current reality comes from the omnipresence of devices with poor sound reproduction quality. Will this be bad for music that excels in musical and sound quality? Or, on the contrary, will it awaken an audience that would want better quality?

On the one hand, we can assume that music influences people and societies. On the other hand, we can admit that music is modified because people and cultures change. Therefore, it is genuine to fear that if the classical concert experience loses all its identity, it not only does not win a new audience but also loses the people used to traditional concerts. The question these changes will answer is: for a classical music concert, how much does music matter compared to everything else?

Say ¡Holla! to fellow attendees, subscribers, and sponsors.

Now let's go to the main subject: how to dress for a classic concert today?

Comfortable; also respectful

You should consider three specific limits when dressing up for a classical music concert: the limits laid out by the concert halls (usually on their websites), what common sense recognizes as decent, and legal boundaries.

With that considered, you can go dressed as you want!

You can trust me because that's what Brazilian orchestras and orchestras from abroad, concert halls, and writers say (and they say it so similar to how everyone else says it makes us think of the late-20th-century American poet Copy McPasteson). They say something like this:

It is important that the audience feels comfortable. Most people consider going to a classical music concert memorable and tend to dress for the occasion. Some people come to the hall directly from work, dressed professionally. Formal attire – evening gowns and tuxedos – is generally worn only to gala events and fundraising days.

Some go further and even say there is no dress code.

Often concert halls and orchestras also ask for some decorum. For example, the Brazilian Symphony Orchestra (Orquestra Sinfônica Brasileira – OSB), located in the sunny and beachy Rio de Janeiro, asks the public to avoid wearing shorts, flip-flops, and swimwear.

The Austin Symphony also asks the public to moderate the use of perfumes. They argue that too many smells can disrupt the delight of those close to the fragrant person and may disrupt even the enjoyment of the scented person himself. As funny and quaint as this request is, it would be worse if they had to ask the public to wear (more) perfume.

We can conclude that regarding concerts and operas – the context we are considering – you should dress comfortably and try to prevent your presence from annoying other people.

As the canonical male fashion reporter Gay Talese puts it: “I dress as a sign of respect for whom I will interview, whomever the interviewee is.” Following this good lesson, we can arrive at this synthesis: let us all dress to show respect for the people who will see us, whomever they may be.

And it makes sense that we take care of our comfort while respecting other people’s comfort: you go to a concert to enjoy the music. For this, here are some simple and practical choices.

Objects: Take and keep the minimum.

You should have a way or place to store your personal belongings, such as wallets, mobiles (and accessories), keys, etc. If your outfit does not have pockets, take a bag. There are also handbag options for men. If you choose to wear clothes with pockets, consider that many concert halls are old and have smaller seats than, for example, new movie halls. Hand-holding objects commonly cause noises. Once, I saw a confused boy trying to decide whether to hold his belongings or his girlfriend's hands. Carrying a large set of keys into the concert hall is rarely necessary.

Fabrics: go suave.

Noise can also come from the fabrics of clothing. Thick synthetic materials are noisy. Most concert halls have lockers where you can leave raincoats, for example. Well, even Bruce Wayne leaves his cape when he goes to concerts. And it's not just to avoid noise; it’s for you to feel comfortable. There are long concerts – two hours of hassle is too much hassle.

Fitting: minus is minus.

Even the best fabric in the world is perceived as a hassle if the clothing is tight enough.

To the one who lifts weights: the results of the hours at the gym can wait to be displayed. So, take it easy. We understand your pride.

Too much skin is also upsetting. A short skirt can put intrusive looks at intimate things in a modest context.

In an ideal world, one could wear a pajama suit to classical concerts.

Context: only the prima donna should look like the prima donna

Professional positions and typical concert figures are few, distinct, predictably dressed, and have specific functions. Therefore, it is essential to consider who they are before choosing what to wear. A true story: I witnessed a clumsily clad young man resembling the theater ushers. While he waited for the concert to start or for someone to arrive (I did not know for sure), he was pestered several times by people asking about the location of their seats and things like that.

Other typical figures we can see are the maestro and his suits; soloists and their bright clothes; musicians and their black suits with pre-Armani shoulder pads or black robes in general; organizers of external parking areas; internal area crew.

Unless you deliberately want to be confused with these figures, it is wise to dress differently from them. I, oblivious to this aspect, was once led by a security guard to the musicians’ entrance when he was calming a little confusion in the entrance queue, and I ended up missing half of a concert I had longed to see.

Coda

Clothes must be a good fit for you to go to a concert. There is no digital experience that replaces the magnitude of authentic live music.

Nothing should impede attending classical concerts because classical music offers unique experiences!

Especially if you are young, attending classical concerts brings advantages to conversations and conviviality. It brings benefits even to love matters: knowledge and intelligence always help with flirting. They always help with everything. By going to these concerts, you will stand out among those who don’t, because these young people, for the moment, are the majority. Maybe that person (you know who) will even get more interested in you when you mention how fun it was to listen to such an extraordinary repertoire and to go to that beautiful concert hall.

If you have questions about how to dress, go to the halls anyway and see what kind of clothes people have been choosing. There are always viable options, whatever your style. For example, as Eleonore von Breuning knew, “one of the most admirable girls in Bonn,” Beethoven loved Turkish Angoras' wool knitted vest.