D. Pedro I of Brasil, IV of Portugal - Anthems and Imperial March

10/03/2021 - Alberto José Vieira PachecoISBN: 978-65-994082-0-5

Introduction

It is well known the life of the statesman D. Pedro I of Brazil and IV of Portugal (Queluz, 12/10/1798 – 24/09/1834). Likewise, its importance in Luso-Brazilian history is attested by any schoolbook. On the other hand, his musical production was eventually eclipsed by his political activity and still waits to be evaluated and studied exhaustively. In this context, this publication is intended as a contribution to better know the work of this important musical figure.

First of all, it is necessary to make a brief presentation of the "musical life" of the emperor1. His musical training may have begun whilst he still lived in Portugal. His main and most constant teacher was Marcos Portugal2 (1762-1830), but it is very likely that he had received lessons from other music teachers as Giuseppe Totti3, Luisa Piot4, father José Maurício Nunes Garcia5, Arvelos Januário da Silva, the father, and Sigismund von Neukomm. His commitment to musical studies earned him great fruits. It is common to say that he sang well, conducted, and played various instruments such as piano, flute, clarinet, violin, contrabass, trombone, harp and guitar. However, his performance as a composer was one that deserved the most applause.

Examples of his religious music can be seen in Acervo Musical do Cabido Metropolitano do Rio de Janeiro6:

1. Responsório para São Pedro de Alcântara (Mortuus est)7

2. Antífona de Nossa Senhora, em Dó maior (Sub tuum praesidium)8

3. Credo do Imperador (Credo, Sanctus e Agnus Dei da Missa de Nossa Senhora do Carmo, em Dó maior)9

4. Hino de Ação de Graças, em Dó maior (Te Deum)10

The presence of these scores in the collection makes it possible that they had been performed on many occasions, in the Brazilian Imperial and Royal Chapel.

The King-Emperor also ventured into theatrical music. In 1831, on his visit to Paris, when he sought political and military support to regain the throne of Portugal from the hands of D. Miguel I, he had his own music performed at the Italian Theater. The performances, which deserved the direct support of Giocchino Rossini (1792-1868), received, mostly, very favorable reviews.

Inevitably, he also composed music for piano, or chamber/salon music. In this case there are a Marcha fúnebre and a Souvenir Filial or Divertimento, both compositions for piano published by Pierre Laforge, in Rio de Janeiro in 1837. Unfortunately it was not possible to locate these scores. The works presented in the present publication lie in this context of the chamber music, or of arrangements for chamber group. Although some songs have been composed for military contexts or for higher proportion festivities, they end up becoming mandatory in the salon repertoire, in the piano and voice format. So they will be published here using this instrumentation, with the only exception of the Hino a D. João IV, of 1817. As there is no full publication of this piece, we judge it important to include here an edition of the original orchestral version, from which we elaborate a piano and voice arrangement.

It is important to emphasize that D. Pedro had a great success in producing patriotic music. An interesting example is the composition known nowadays as Marcha de Ituzaingó, which would have been written, in 1827, to be used by the Brazilian troops in the war against the Províncias Unidas do Rio Prata (today known as Argentina). The march is still performed in the official acts in which the president of Argentina takes part, announcing his arrival11. The tradition of that country has D. Pedro as the possible composer, although this authorship is not taken for granted.

There is no doubt, however, that the patriotic and political anthems are the most influential and longevous compositions. The four known anthems of this composer are published here. This set could include the Hino Maçônico Brasileiro (Brazilian Masonic Anthem). However, despite being known the relationship between D. Pedro and the Freemasonry, there is no consensus about the authorship of the music and lyrics of that anthem. The poor circulation of documents related to this closed and secret society makes it difficult to access any information, and it was not possible to consult any score. In fact, the Masonic researcher Rodolfo Rup12 says the oldest musical source located is a publication of 1936, which is too late and without any authorship indication.

1. Hino a D. João [Anthem to D. João]

This is the first D. Pedro’s anthem, composed in 1817, in Rio de Janeiro. The year before, D. Maria I had died, which finally left room for the beginning of the D. João’s reign, who previously played the role of regent on behalf of the Queen, considered hopelessly insane since 1792. Therefore, it is very likely that this song is a gift from the prince to his real father, in celebration of the beginning of his reign, so it will be called hear as Hino a D. João. The anthem can also be related to the, thus known, Revolução Pernambucana (Pernambuco’s Revolution), of emancipationist and republican character, which erupted in March of that year. That is, the composition, besides being a song of patriotic exhortation to the King, may be an answer to the rebels from Pernambuco, or even a song commemorating the flop of the revolution. The only known specimen of the anthem is kept in the National Library of Portugal and it is a score for orchestra and choir, which was never published in full, nor has a modern edition. So a piano version was prepared by this author.

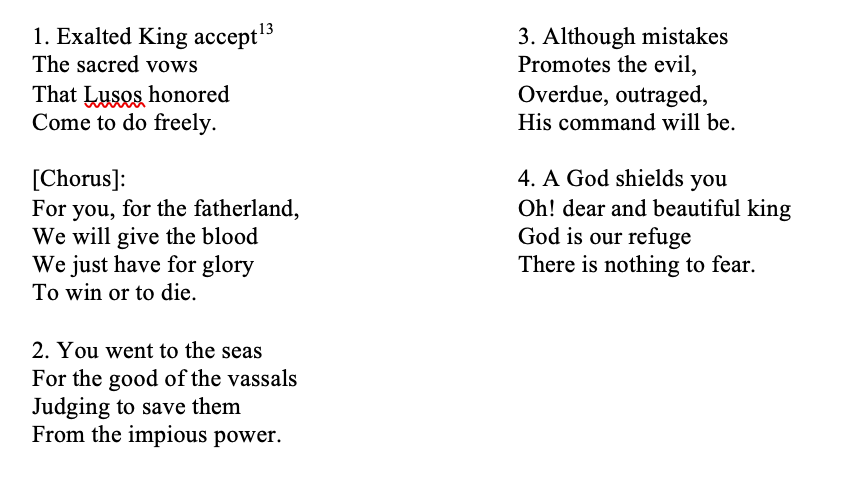

The following text is presented in the manuscript:

The same text is used by Marcos Portugal to compose his famous patriotic anthem, considered the first Portuguese National Anthem. This is a rare example of a poem of anthem being used by different composers. This fact and the very scarcity of sources made this anthem to be rarely mentioned and the little that has been said is full of misconceptions. For example, Ayres de Andrade denies even the existence of the anthem, considering it as only a version of Marcos Portugal composition, based exclusively on the use of the same text. Andrade seems to have had access only to the text transcription offered by Ernesto Vieira, otherwise he would not have made this statement if he had consulted the musical manuscript. After all, the musical sources leave no doubt that they are different compositions. In his turn, Vieira confuses this with the D. Pedro’s Hino Constitucional, sung in Lisbon in 1821 to commemorate the Portuguese constitution, which we'll discuss below.

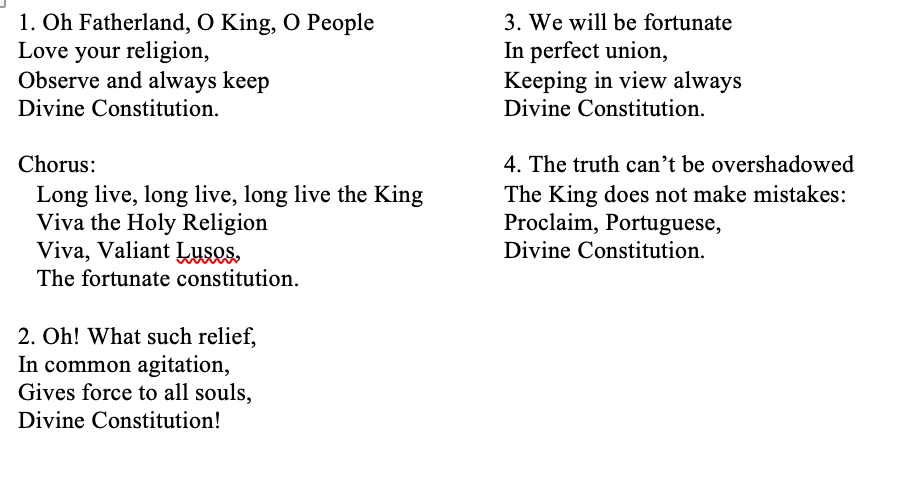

2. Hino Constitucional, or da Carta [Constitutional Anthem]

As its title indicates, this anthem is inserted within the spirit of the liberal revolution of 1820 that demanded a constitution to Portugal. It also became known as Hino da Carta (Anthem to the Constitutional Charter) by direct association to the Portuguese Constitutional Charter of 1826. Composed in Brazil in 1821, it is among the more successful Luso-Brazilians anthems, because it was officially instituted as the Portuguese national anthem until the proclamation of the Republic in 1910.

The earliest known source of this anthem is a booklet of the poem, which informs it has been made “on 31st March, 1821”14. Despite not being able to locate the document, it is cited in the Bibliografia da Impressão Régia do Rio de Janeiro15, and transcribed by Andrade16. The anthem quickly gained popularity in Brazil, as shown in the Gazeta do Rio de Janeiro which documents the celebration made in the São João Royal Theater to commemorate the anniversary of D. João VI, on 13th May 1821, when the “Constitutional anthem, whose lyrics and Music is an estimable gift, that His Royal Highness offered to the Portuguese”17, was performed. It is interesting to underline that in news about a ball held on 24th August of the same year18, the newspaper also attributed to D. Pedro the authorship of the poem. César das Neves agrees with this19, for, after transcribing in his songbook the same text quoted by Andrade, says to have “a copy of the sheet handwheel in which this poem was printed with the following title: Hymno Imperial Consitucional composed by D. Pedro, in 1822”. Anyway, it is not surprising that D. Pedro ventured as poet of a anthem. After all, as noted by his biographer, Eugenio dos Santos20, he sought to “make himself heard as a poet, too”.

Although composed in Brazil, the anthem quickly came to Portugal where, according to Benevides21, was released on 24th August 1821. Maria José Valentim reports that the text was first published in Oporto, in the same year, under the title of Hymno Patriótico22. The fact is that, with such success, the text of the anthem received other editions already in 1822, in the same city23. One of them, titled Hino Imperial Constitucional, probably comes from the “sheet handwheel” quoted by Neves, and configures the earlier primary source that was possible to see:

It is natural that these first editions have been given in Oporto, the city where the Portuguese liberal revolution began. Without taking into account these documents, Vieira gave rise to the mistake that the anthem would be released in Portugal not before 1826, the year when the Portuguese Constitutional Charter was granted. The author defends the idea that the D. Pedro’s anthem sung previously in Portugal would be that one of D. João, in 1817. This theory has no foundation. The text of the Hino a D. João VI has no constitutional characteristic and in no way resembles the one printed, both in Brazil and in Portugal, in 1821-22, and that is actually used in Hino Constitucional or da Carta. Thus, there is no doubt that the Hino Constitucional was already known in Portugal shortly after its debut in Brazil.

The oldest known musical scores are from the end of the 1820s24. The first printed version seems to be the one that is presented in the form of handwritten copy kept in the Public Library of Évora. The copyist said the original was edited by the widow Waltmann. This lady began her editing work in 182525, but she was already bankrupt in 182726, which would place the print between these years. However, as D. Pedro is now referred to as "King of Portugal", the edition has to be after the death of D. JoãoVI, in March 1826, and before the bankruptcy of the publisher, in 1827. It is worth drawing attention to a manuscript version of the anthem, whose instrumental part would be an arrangement made by Marcos Portugal27. This shows that before 1830 the piece already had an orchestral version not yet located, and shows that Marcos Portugal followed closely the musical production of the illustrious student. Other versions for military band can be found in Portuguese archives, as it would be expected in the case of a anthem that achieved official status28.

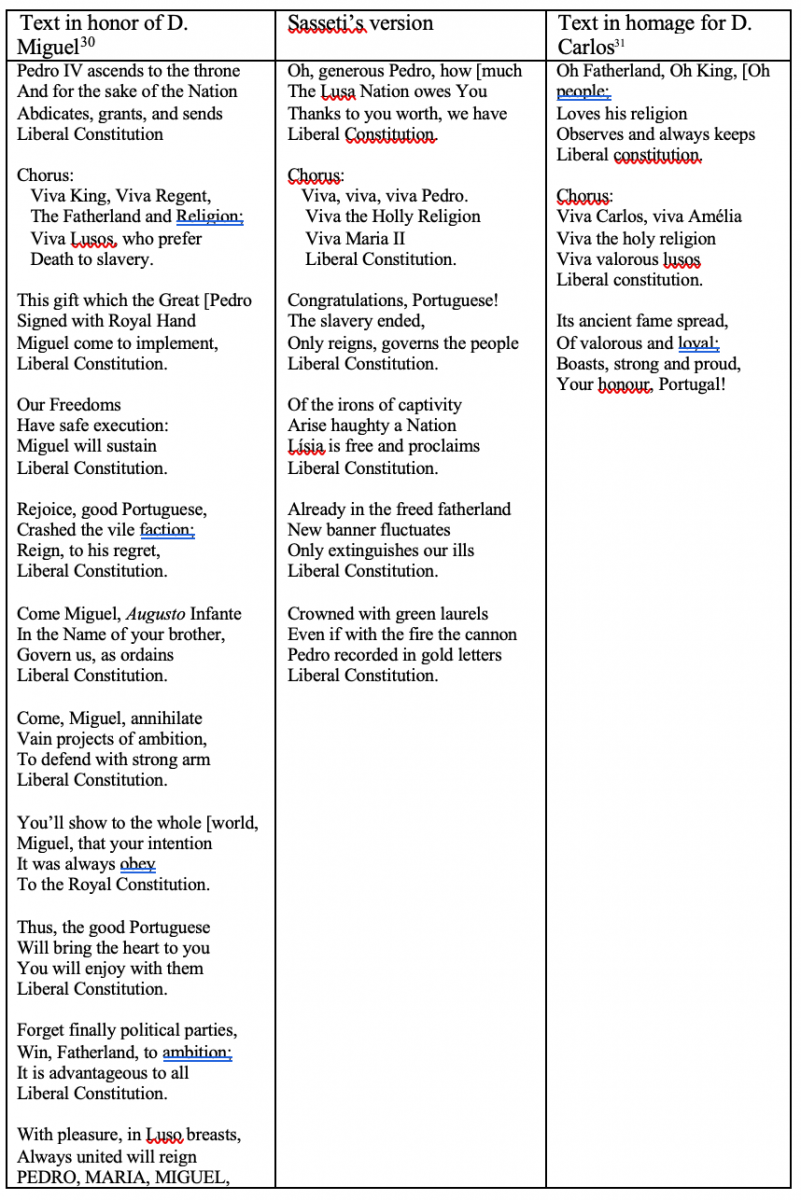

As might be expected the success and longevity of the anthem resulted in a series of counterfeits. There is no reason or space to name them all here, but we can call attention to some. Somewhat unexpected is that one made for “the next coming of H.H. the sereníssimo Prince D. Miguel to rule these kingdoms”, whose text was to be sung with the music with the Hino Constitucional. It is an irony of fate that D. Miguel, honored here by the more successful constitutional anthem, eventually resumed the Absolutist Regime shortly after his return to Portugal. By mid-century, Sasseti publishes another version in their series Hymnos Nacionaes Portugueses. In this case the text is fully associated with D. Pedro himself and his heir, D. Maria II, great names of liberalism. Another interesting example is the version made in honor of D. Carlos I and D. Amélia. This is a score for large orchestra, including drums and solo voice, that is, an orchestration in accordance with their own time. In this regard it is important to stress that, in 1893, in his own edition of the anthem, César das Neves29 remembers that it is “adopted by H.M. D. Carlos I” as a personal anthem.

The important thing to highlight is that each monarch ended up being honored with a series of anthems, from various authors, some with varying degrees of success and/or officiality. Despite this, the Hino Constitucional could survive the “competition”, adapting to the situation. On the other hand, regardless of the adaptations, the fact that the anthem was to be associated, from the beginning, to the constitution and, consequently, to the Portuguese “nation”, made it more permeable to the succession of the kingdoms.

Adopted as national, the anthem ended up winning a series of musical editions in various types of presentation and instrumentation, even being used as theme for autonomous works. One might call attention, for example, to versions for solo piano, or band, and even to instrumental variations, such as that one in four numbers, composed by Theofilo Russel32. Another notable example are the variations composed by João Domingos Bomtempo – last movement of his Sérénate, kept in the National Library in Lisbon33. The anthem deserved attention even outside the Lusophone space, as shown in the version made for piano by Ferdinand Beyer (1803-1863) and which is kept in the Library of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Madrid34. In the same library you can consult a version for large orchestra35 made by Tomas Breton y Hernandez (1850 -1923). Apart from the Iberian Peninsula, there is, for example, the following information:

LONDRES. On lit dans le Court journal du 9 juillet: “Siroe, opéra de l’honorable miss Marianne Jervis. Une seconde répetition de cette intéressante et remarquable production a eu lieu, mardi dernier, dans les salons de Madame Cuthbert, Grovenor square. Elle a été honorée de la présence de don Pedro et d’un nombreux cercle d’amateurs distingués (...) La soirée s’est terminée par l’hymne constitutionelle de la composition de don Pedro, qui a produit un très grand effet36 (Revue Musicale, 06-10-1831).

Remarkable are also the variations for piano made by Charles Bénet and published in Paris37:

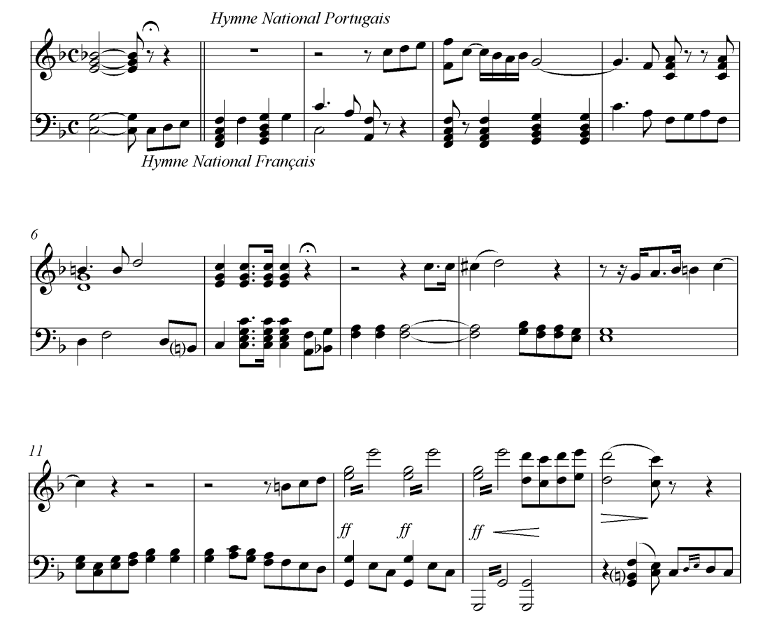

Fig. 7, excerpt from Variations pour piano sur l'Hymne National Portugais de Chales Bénet38

In this passage we see that the composer puts into dialogue two great symbols of liberalism: the Marseillaise and Hino Constitucional of D Pedro.

3. Hino da Independência do Brasil [Anthem of the Independence of Brazil] (or Imperial e Constitucional [Imperial and Constitutional])

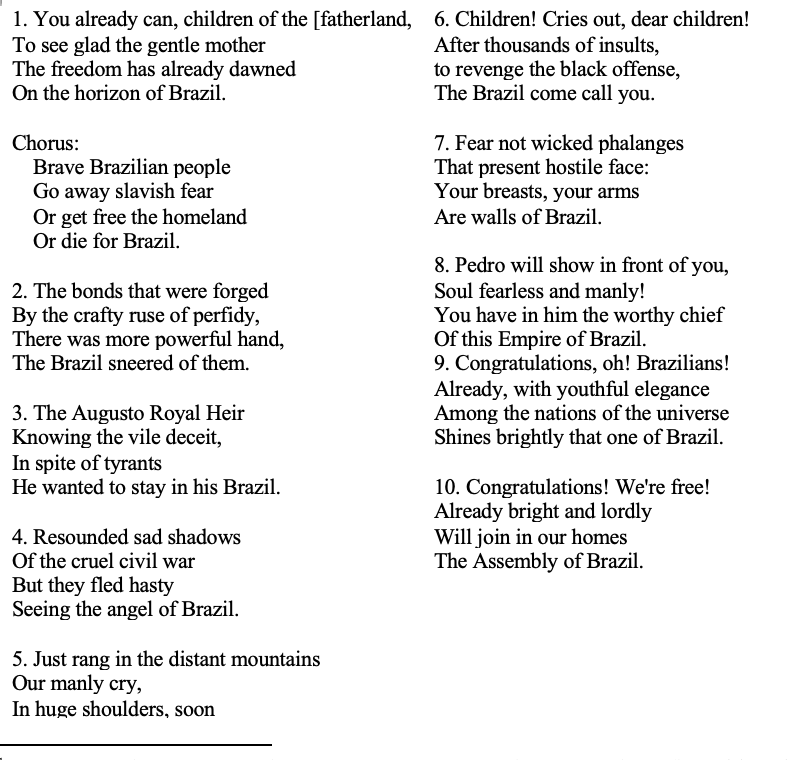

This song makes uses of the same text used by Marcos Portugal to compose his independence anthem. The oldest handwritten version is the one that is kept in the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro [Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute] (IHGB), in Rio de Janeiro, donated to that institution in 1861 by Francisco Manuel da Silva, who assured that the score is an autograph – the fact remains without confirmation39. As Lino de Almeida Cardoso40 reminds us, in the text that must be the most recent about this anthem, in the earliest printed sources, the composition is referred to as Hymno Imperial e Constitucional41. This edition lies between the first ones of the Brazilian press. On the other hand, this title shows that the musical piece in itself was strongly related to the constitutional liberal movements, following the example of the poem that was originally published under the title of Hino Constitucional Brasiliense42. The text is of the Brazilian journalist, politician and poet Evaristo Ferreira da Veiga43 (1799-1837), written in Rio de Janeiro, on 16 August 1822:

The scores usually bring only the first four stanzas (besides the chorus), but nothing hinders the music to be applied to the others. The tradition consecrated the idea that the music had been composed on September 7, 1822. However, many authors have put this idea into question. It has also been quite widely discussed the historical precedence of this in relation to the homonymous anthem composed by Marcos Portugal. Andrade44, for example, does not confirm which one would have been the first to be composed, but proves that one of Marcos Portugal would have been the first to be sung in Rio de Janeiro. Also, in the first decades, the anthem of the maestro would have been associated with celebrations of independence, while the anthem of the emperor would have been used as the "national anthem" at other events at least until 1831, when it began to suffer competition from the current Brazilian national anthem45. In turn, Cardoso46 wants to believe in the historical precedence of the anthem of Marcos Portugal. We will not enter into this debate because it would not be possible now to add anything concrete. Anyway, for this text, a brief historical precedence of one or another anthem is less relevant.

The D. Pedro’s composition is still today the official Anthem of the Independence of Brazil. Already at the edge of its bicentennial, the anthem had to suffer some adjustments and adaptations in music and text. The official version can be consulted in the site of the Brazilian Government. One can see, with regard to the text, only the chorus and the verses 1, 2, 7 and 9 remain in use, without major changes, except the first verse of the poem, which is slightly changed from “Já podeis filhos da Pátria” to "Já podeis da Pátria filhos”.This was probably done in an effort to improve the prosodic relationship between text and music, or an attempt to avoid any bad puns that the original might suggest. As was to be expected, the omitted stanzas are the most conjunctural and refer, for example, the development of a Brazilian constitution, or the fact that D. Pedro decided to stay in Brazil, although he received the reverse order from Portugal. The choice of some verses over others actually moves the text from the historical reality in which it was written and put it on a timelessness plane so important to the national symbols. In turn, the music suffered several adjustments, which was already noticed by Cardoso47. It is enough to compare the anthem, here edited from the edition of Walsh (1830), with any more modern recording or score to see the modifications both in the instrumental and in the vocals. This phenomenon of adjustment, simplification and/or modernization can be identified in other editions that are intended for a wide and lay audience. However, in this present publication, we seek to maintain ourselves as close as possible to the original versions of the songs. Thus, we will take into account the Walsh edition, the first one for piano and voice that could be consulted, which is very close to the to the handwritten orchestral version, donated by Francisco Manuel da Silva.

4. Hino Novo Constitucional [New Constitutional Anthem] (of Amélia, or of D. Pedro IV)

It was initially known as Hino Novo Constitucional or Hino da Amélia for having been composed on board the corvette of the same name48. According to Neves, in the late nineteenth century it was called Anthem of D. Pedro IV and “the military bands play it in all festive or funereal solemnities, that are related to that monarch”. Vieira49 affirms that it would have been “at first time performed on S. Miguel, on 23 June, 1832, when the expedition got together at Relvão Camp for boarding [destined for mainland]”. That is, the anthem was composed when D. Pedro – who had renounced the Brazilian throne in favor of his son Pedro, and the Portuguese in favor of his eldest daughter – was preparing to occupy the Oporto. It was an important time of the Liberal Wars. This civil conflict would withdraw the throne from D. Miguel and would restore the right to the crown to D. Maria. The relationship with the war gave almost immediate popularity, in Portugal, to the anthem and associated it closely with D. Maria II50. So it ended up deserving some editions, for voice and piano and also just for instruments51. Among the oldest is the one published in Lisbon by Ziegler, and another one published in Paris by Pacini52. It was possible to locate only the piano solo version of the Ziegler’s edition. However, a probable handwritten copy of the voice and piano edition53 is available in the spoils of Filipe de Sousa in the Jorge Álvares Foundation, Alcainça54:

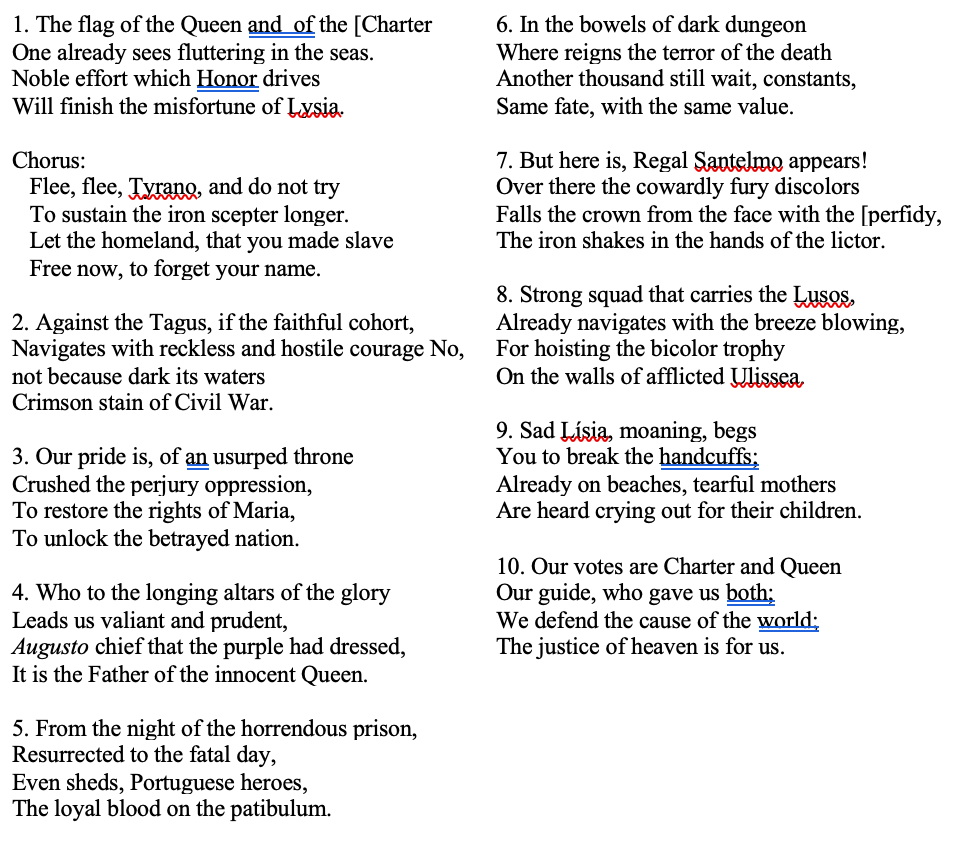

The text would have been printed and distributed among the rebels shortly after being written. This was possible because, according to Valentim55, “it is known that D. Pedro brought a lithographic press in his luggage when he arrived [at Oporto]”. This author transcribed the older edition of the poem that she could consult and which would have been published by Gandra, in 183356:

In turn, Neves57, without providing a justification, transcribed those that would be the four original stanzas of the original anthem, attributing its authorship to D. Pedro and, in a footnote, quotes some other stanzas that would have been written later. In fact, the supposed original verses quoted by Neves are the 1st, 8th, 9th and 10th, and the spurious are the 2nd to 7th, which are in the present edition of Gandra transcribed above. Neves also states that such original stanzas were authored by D. Pedro. Vitorino Nemésio58, in turn, informs that Luís da Silva Mouzinho de Albuquerque (1792-1846) would be the author of the verses. However, it was not possible to consult a primary source which confirms the authorship of the poem. On the other hand, the original stanzas of Neves are the same transcribed in that handwritten copy kept in Filipe de Sousa’s spoils. Thus, it is likely that the original poem was written as it was published by Gandra, but only four of its stanzas were used in the Ziegler’s edition – as we seen, a similar phenomenon occurred with the text of the Independence Anthem. In turn, the version of Sassetti, that was included in the series Hymnos Nacionaes Portuguezes [Portuguese National Anthems], makes its own of contribution to the text, raking a stanza to the four generally used in the musical editions59. To conclude, it is necessary to say that the inclusion of the anthem in the Sassetti series established this as the third and last anthem of D. Pedro which gained the privilege of “national”.

5. Imperial March

This composition uses a four-hand piano and clarinet. There is no information about this composition besides the original manuscript that is kept in the National Library of Portugal and that is, therefore, the only known source60. Taking into account the specific characteristics of the genre, it is quite likely that the march was written originally for band, and that this version is a later arrangement. The writing of the composition is quite simple and it is possible to assume that, in this format, it had been used in a domestic and familiar environment. After all, the emperor played clarinet and could have produced this score to be accompanied on piano by his daughters and/or wife. These are assumptions that are based on what it is known about the everyday music of the imperial family.

The document was offered to the National Library in Lisbon, but it was not possible to find out who had been the previous owner. It may be that the score has belonged to D. Amélia, the second wife of D. Pedro, who died in Lisbon, 1873. After all, it is known that the Empress gave some scores to the Palmela family61 and, in the same way, she could have offered the manuscript in question.

References

[1] An extensive musical biography can be found at: Pacheco, Alberto José Vieira. “D. Pedro I do Brasil, IV de Portugal”. In.: Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas. Lisboa: Caravelas, 2012. Available at: Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas

[2] Marques, António Jorge. “Portugal [Portogallo], Marcos [Marco] António (Da Fonseca)”. In.: Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas. Lisboa: Caravelas, 2012.

[3] Pacheco, Alberto José Vieira; Fernandes, Cristina. “Totti, Giuseppe di Foiano”. In.: Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas. Lisboa: Caravelas, 2010

[4] Fernandes, Cristina. “Piot, Luísa”. In.: Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas. Lisboa: Caravelas, 2010

[5] Figueiredo, Carlos Alberto. “Garcia, José Maurício Nunes”. In.: Dicionário Biográfico Caravelas. Lisboa: Caravelas, 2012

[6] Cabido Metropolitano do Rio de Janeiro

[7] Available at Cabido Metropolitano do Rio de Janeiro - SM53

[8] Available at Cabido Metropolitano do Rio de Janeiro - SM53

[9] Available at Cabido Metropolitano do Rio de Janeiro - SM54

[10] Available at Cabido Metropolitano do Rio de Janeiro - SM55

[11] The music can be heard at: Youtube - Marcha

[12] Rup, Rodolfo. “O Hino Maçônico Brasileiro”. Available at HIno Maçônico Brasileiro

[13] Literal translation

[14] Hino Constitucional feito aos 31 de Março de 1821, e oferecido á Nação Portuguesa pelo Príncipe Real, seu author. Rio de Janeiro: Impresão Régia, 1821.

[15] Camargo, Ana Maria de Almeida; Moraes, Rubens Borba de. Bibliografia da Impressão Régia do Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo: Edusp, Libraria Kosmos Editora, 1993.

[16] Op. Cit., Vol. 1, p. 141

[17] “In the evening, Their Royal Highnesses the REGENT PRINCE and the ROYAL PRINCESS saw fit to honor with Their Presences the São João Royal Theater, which was adorned and illuminated with richness and elegance; [...] Soon, a Dramatic Praise (Elogio Dramático) was performed, alluding to the sadness that HIS MAJESTY absence had left in all hearts, and the most just motive for consolation by the Royal Presence of His Heir, in which appeared the Portraits of TM and TRH, the REGENT PRINCE and the ROYAL PRINCESS, to whom was rendered the same reverent applause; and the musicians singing Hymno Constitucional, whose lyrics and Music are an estimable gift that HRH offered to the Portuguese” (Gazeta do Rio de Janeiro, 16/5/1821, available at: Gazeta do Rio de Janeiro - 16/05/1821). News located by Andrade (Op. Cit., Vol. 1, p. 143) and transcribed here from the original.

[18] “[...] so sang the constitutional anthem, whose lyrics and music were composed by HRH”. News located by Andrade (Op. Cit., Vol. 1, p. 143).

[19] Neves, Cesar A. das. Cancioneiro de musicas populares: collecção recolhida e escrupulosamente trasladada para canto e piano por Cesar A. das Neves. 3 vols. Porto: Typ. Occidental, 1893-1899. Vol. 1, p. 43 [Available at: Cancioneiro de músicas populares]

[20] Santos, Eugénio dos. 2008. D. Pedro IV: liberdades, paixões, honra. Rio de Mouro: Temas e Debates & Printer Portuguesa.

[21] Benevides, Francisco da Fonseca. O real Theatro de S. Carlos de Lisboa, desde sua fundação em 1793 até a actualidade. Lisboa: Typografia Castro Irmão, 1883. p. 124 [Available at: O real theatro de São Carlos]

[22] Hymno Patriótico. Porto: Off. de Viúva Alvarez Ribeiro & Filhos, 1821. Information at: Valentim, Maria José Quaresma de Carvalho Alves Borges. A Produção musical de índole política no período liberal (1820-1851). Master dissertation. Lisboa: Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2008. However, the author does not indicate the location of the source of the anthem in question.

[23] The Hino Imperial Constitucional do Senhor D. Pedro that is in the back of the Hymno dedicado Á senhora Infanta D. Izabel Maria, pela musica do Hymno Imperial do Senhor D. Pedro (P-Ln, cota L. 10792//15 P.) and the Hymno Patriotico cuja letra e a musica he da composição do sereníssimo Principe Real o Senhor Pedro de Alcantara (P-Ln, cota L. 10792//16 P.).

[24] Without making an exhaustive list, some examples of sources can be gathered: i. Hymno de S. M. I e Constitucional O Serenissimo Sr. D. Pedro de Alcantara. Cantado no Anno de 1826 no R. Theatro de S. Carlos. (Handwritten music, P-Ln, call mark MM 341/6) [available at Hino Constitucional]. ii. Hymno Portuguez. P-Ln MM 340//2 iii. Hymno Constitucional composto Por S. M. I. o Snr. D. Pedro de Alcantara Rei de Portugal Lisboa No armazen de música de viúva Waltmann e Filhos rua direita de S. Paulo Nº 18 (handwritte copy, P-EVp, call mark Cód. CLI /2-9 nº 7). It was not possible to locate the printed original. iv. Hymno da Carta in Neves, 1893-99. v. Hymno da Carta Constitucional. Lisboa: Sassetti & Cª, s.d. (P-Ln, cota M.P. 449//42 A.)

[25] As can be see in: Albuquerque, Maria João Durães. A edição musical em Portugal (1750-1834). Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 2006. p.131. Or in the file of Évora University: http://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/bitstream/10174/2812/7/EMERG%C3%8ANCIA%20MERCADO_Cap.6.pdf

[26] As the document of the Torre do Tombo shows: http://digitarq.dgarq.gov.pt/details?id=4522419

[27] Hymno Constitucional Offerecido a Nacão Portugueza Pello Principe Real Arranjado Para Piano Forte Por Marcos Antonio Portugal. (Música manuscrita, P-Ln, cota M.M. 340//8.) [Available at Hino Constitucional].

[28] For example, the library of the Palácio da Ajuda, in Lisbon, holds a manuscript of the anthem for band: Hino da Carta Constitucional da Monarquia Portuguesa – entry 4590 in: Santos, Mariana Amélia Machado (org.). Catálogo de música manuscrita [da biblioteca do palácio da Ajuda]. Lisboa: Biblioteca da Ajuda, Ministério da Educação Nacional, 1958-68, 9 vol.

[29] Op. Cit. vol.1, p. 42. Here it is also possible to consult other versions of the anthem’s text.

[30] “By a Vate Aveirense, in the [journal] Periodico dos Pobres” (P-Ln, call mark L. 10792//22 P.)

[31] Hymno Portuguez (Handwritten music, P-Ln, call mark M.M. 340//2). (The tribute to D. Carlos I ends up situating the specimen between 1889, the year of acclamation, and 1908, year of regicide).

[32] A Sua Magestade El-Rei D. Carlos I. Hymno da Carta transcripto e variado para piano por Theofilo de Russel. S.l.: Editora Adm. J. Guedes, [ca 189-?] (P-Ln, call mark c.n. 1129 a.)

[33] There are two versions available, in the form of quintet and septet (P-Ln, cotas: C. I. C. 48; C. N. 702), respectively nº B75 e B75a in the Bomtempo’s catalog (in: D’Alvarenga, João Pedro. João Domingos Bomtempo, 1775-1842. Lisboa: Instituto da Biblioteca Nacional e do Livro, 1993. Available at: Catálogo de Bomtempo). In the same catalog the author states that the work was composed in “Lisbon, 1821 or later”.

[34] Hymne constitutionnel du Portugal Transcription de Ferd. Beyer. S.L.: s.n. (Handwritten music, Library of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Madrid).

[35] Himno Portugues de la Carta. Bretón (Handwritten music, Library of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Madrid).

[36] LONDON. We read in the newspaper Court of 9 July: “Siroe opera of the Honourable Miss Marianne Jervis. A second Repetition of this interesting and remarkable production took place last Tuesday, in the salons of Madame Cuthbert, Grovenor Square. She was honored by the presence of Don Pedro and a large circle of distinguished amateurs (...) The evening ended with the constitutional anthem of the composition of Don Pedro, who produced a great effect (Transcription given at: Cardoso, Lino de Almeida. O Som social: música, poder e sociedade no Brasil (Rio de Janeiro, séculos XVIII e XIX). São Paulo: Edição do autor, 2011. p. 282)

[37] A sa Magesté très fidèle Don Carlos 1er Roi de Portugal. Variations pour piano sur l'Hymne National Portugais (Théme du Roi Don Pédro 1er) par Charles Bénet. Paris: Louis le Signe, s.d. (F-Pn)

[38] The natural sings in brackts are sugested by us.

[39] Hino à independência do Brasil posto em Música para canto e grande orquestra. (IHGB, call mark DL987.008; photographic copy in: lata 987, pasta 8).

[40] Cardoso, Lino de Almeida. “Subsídios para a gênese da imprensa musical brasileira e para a história do Hino da Independênciai, de Dom Pedro 1”. Per Musi, Belo Horizonte, n. 25, 2012.

[41] Hymno Imperial e Constitucional composto por S. M. I. o Senhor Dom Pedro 1º (in Walsh, Robert. Notices of Brazil in 1828 and 1829 by the Rev. R. Walsh. 2 Vols. London: Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis, 1830. Vol. 2, p. 533. [Available at: Hino Imperial e Constitucional]). Hino Imperial e constitucional. Rio de Janeiro: Ferguson e Crockatt, 1824. (Information given at news from Diário Mercantil. No specimen could be located).

[42] The manuscript is in the Manuscripts Section of BR-Rn. The oldest printed version, that was possible to consult, is: Hymno Constitucional Brasiliense. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia do Diario, 1822. (BR-Rn, call mark DIORA 248, 4, 7 n. 15).

[43] This poet is author of other anthems such as: Hymno do batalhão do imperador, Hymno Marcial, Hymno braziliense (in: 1. Moraes Filho, Mello. Serenatas e Saraus: collecção de autos populares, lundús, recitativos, modinhas, duetos, serenatas, barcarolas e outras produções especialmente brasileiras antigas e modernas. Com uma nota explicativa dos assumptos de cada volume por Mello Moraes Filho. vol. III Hymnos / modinhas diversas. H. Garnier: Rio de Janeiro; Paris, 1902 (P-Ln, call mark L. 10234 P.). 2. Silva, Joaquim Norberto de Sousa e. A Cantora brazileira. Nova collecção de hymnos, canções e lundús tanto amorosas como sentimentais precedidas de algumas reflexões sobre a musica do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Pariz: H. Garnier, s.d.). Independência ou morrer. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia do Diario, 1822. (BR-Rn, call mark DIORA 248, 4, 7, n 11).

[44] Op. Cit., Vol. 1, p. 158.

[45] New information gathered by Cardoso (2012, p. 43) shows that D. Pedro's anthem crossed “the 19th century coexisting with other national melodies”. It is important to note that in 1862 the anthem of D. Pedro would gain great prominence in the celebrations of the inauguration of the equestrian statue of the emperor in Rio de Janeiro as shown by the edition Hymno da Independencia do Brazil composto por S. M. I o Sr. D. Pedro I Reduzido da Partitura Original para piano por Francisco Manuel da Silva. Rio de Janeiro: Imperial Imprensa de Música de Filippone e Tornaghi, [1862]? (BR-Rn, cota Império - F-III-41). This publication is the 16th volume of a series made in commemoration of the inauguration of the equestrian statue of D. Pedro.

[46] Op. Cit., 2012.

[47] Op. Cit., 2012, p. 43

[48] “Anthem of Amelia, that was how the author, D. Pedro IV, called the anthem for having composed it aboard the corvette Amélia during his trip to Portugal, to animate and enthuse the 7500 expeditioners who accompanied him” (Neves, Op. Cit., Vol. 1, p. 252).

[49] Op. Cit., Vol. 2, p. 154

[50] For example, as it shows the specimen: D. Maria II Rainha de Portugal. Himno novo Constitucional composto por Sua Magestade Imperial o Duque de Bragança dedicado a Nação Portugueza para piano forte. Lisboa: Valentim Ziegler, 18--. (P-Ln, cota C.I.C. 88 V.)

[51] For example, Hymno da Amelia in Neves (1893-99, p. 249).

[52] Hymno Constitucional da Nação Portuguesa, composto por S. M. I. o Senhor Dom Pedro, Duque de Bragança. Paris: Armazém de Música de Pacini (Valentim, 2008, p. 21 affirms that this score is the Hino da Carta, but the music revels the Hino da Amélia). (P-Ln, cota C.N. 1502//25 A.)

[53] If we compare the copy with the snippet of the version of Ziegler reproduced by Valentim (2008, Op. Cit., p. Lxxix), it is clear that the manuscript reproduces the printed version. Likewise, Valentim transcribed the text used by Ziegler, which is the same used in the manuscript.

[54] Novo Hymno Constitucional dedicado à Nação Portugueza, handwritten copy kept in the spoils of Filipe de Sousa in the Jorge Álvares Foundation, Alcainça, which indicates as the author “S. M. I. o D. de B. [His Imperial Majesty the Duque of Bragança]”. The manuscript was located by Rui Magno Pinto. Interesting it is to call attention to the note contained in this copy: “Made aboard the Frigate D. M. 2 nd”. The information, despite giving a different name to the ship, reiterates the nautical origin of the anthem.

[55] Op. Cit., p. 66

[56] Hymno composto a bordo da Corveta Amelia. Porto: Imprensa Gandra & Filhos, 1833. Unfortunately it was not possible to locate this source, whose whereabouts is not informed by Valentim. So, in this edition, we will use the text in the handwritten copy.

[57] Op. Cit., Vol. 1, p. 252.

[58] Nemésio, Vitorino. “A Mocidade de Herculano”. Vitorino Nemésio: estudo e antologia. Maria Margarida Maia Gouveia (org.). Lisboa: Ministério da Edução e Cultura, 1986. p. 338. [Available at: Biblioteca Digital Camões]

[59] In the lap of beloved homeland Our vote will be fulfilled, Away again the grapeshot sounds We will reap new laurels (in Hymno de Dom Pedro. Lisboa: Sassetti & C.ª, 18--) (P-Ln, call mark M.P. 449 // 47).

[60] Marcha Imperial Composta por S. Mag.de Imp. o Senhor D. Pedro I para Piano a 4 mãos, e Clarinette. Handwritten music (P-Ln, call mark M.M. 4792//1-3).]

[61] More information in Pacheco, 2012, Op. Cit.